Notes on the Autonomy of Architecture

![C McEwan 2013 School-Cemetery [montage] Left: Fagnano Olona School, Right San Cataldo Cemetery, Both drawings by Rossi.](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/c-mcewan-2013-school-cemetery-montage.jpg?w=720&h=513)

C McEwan 2013 School-Cemetery [montage] Left: Fagnano Olona School, Right San Cataldo Cemetery, Both drawings by Rossi.

One place to situate the theme of autonomy in architecture is in Emil Kaufmann’s discussion in the 1930s on the work of Enlightenment architect Claude-Nicolas Ledoux. Kaufmann emphasised formal aspects such as: cubic masses, bare walls, frameless apertures, and flat roofs. For Kaufmann, the isolation of parts, their dialogue as either repetitive or oppositional elements, represented a formal autonomy. Autonomy re-emerged in the 1970s when architects challenged pseudo-scientific and technologically-driven projects, such as: Kenzo Tange’s 1960 project for Tokyo Bay with its raised roadways from which residential units could endlessly aggregate, Buckminster Fuller’s 1962 domed geodesic smog shield over midtown Manhattan, Archigram’s pop-image megastructures like the 1964 Plug-in City, Paolo Soleri’s anamorphic urbanism, and in Italy, Archizoom’s anarchic No-stop City, a continuous urban structure “without architecture.” In projects like these, formal issues are replaced by statistical analyses, technological optimism, and the potentially infinitely extendable, “open-form.” This path of development is opposed by those architects who follow the theme of autonomy in architecture. In recent years, autonomy has been discussed once again in texts by Pier Vittorio Aureli, Michael Hays, Reinhold Martin, and Anthony Vidler. [1]

The introduction of historical critique into the discipline of architecture is a characteristic the theme of autonomy. However, it is complicated by two general positions that refer to the argument about what kind of historical critique is appropriate. One kind of critique proposes an ideological critique of the history of architecture. An examination of all the contributing factors around architectural form, such as the social, cultural, economic and political, in order to understand how architecture is produced through power. The other kind of critique proposes a typological critique of the history of architecture and its formation as the city. An examination of typological-form in order to understand the processes, principles and formal operations that underline the production of form. In particular, the relationship between the form of the individual building as it relates to the wider collective realm of the city, and the history of architecture. It is important to say that both attitudes are independent of one another, but share a commitment to the repositioning of the “I” of architecture to the “us” of the city. Whether through understanding the form and role of architecture within the city as a product of social, cultural, economic and political concern. Or as much for architecture as a product of the historical, urban and typological structure of the city itself. Again, both positions prioritise the collective mind over the individual.

There is a problematic overlap in these positions because architecture supports social, cultural, economic and political aspects and is their concrete manifestation. Thus, architectural form cannot be considered as a single, isolated event because it is bounded by both the material and immaterial reality in which it exists. However, what the theme of autonomy can do, is open a discussion on what it means to view architecture as autonomous. Thus autonomy refers to notions of separation, resistance, opposition, confrontation, and critical distance, which can be instrumentalised by the architect through the production of images, and texts, aswell as buildings. It is worthwhile to note a few specific examples in the recent history of architecture.

Manfredo Tafuri, in Architecture and Utopia bleakly surmised architecture to be an instrument of capitalist development used by regimes of power, thinking it useless to propose purely architectural alternatives. However, he said that it is the conflict of things that is important, insisting on the productivity inherent in separation. In Critical Architecture Michael Hays writes that architecture is an instrument of culture, and also is autonomous form. The former view emphasises culture as the content of built form, and depends on social, economic, political and technological processes. The latter concerns the formal operations of architecture, how buildings are composed, and how architectural form is viewed as part of a continuing historical project. Aureli develops an autonomy thesis in The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture, in which he articulates an engagement with the city through confrontation. Aureli writes that it is the condition of architectural form to separate and be separated. In this act of separation, architecture reveals the essence of the city, and the essence of itself as political form. For Aureli, it is the process of separation inherent to architectural form that the political is manifest.

In the work of Aldo Rossi the autonomy of form produced critical distance between the legacy of modern functionalist architecture and its critique, of which Rossi was a key proponent. To outline an example, we can refer to two projects undertaken in the early 1970s. A school at Fagnano Olona, and a cemetery outside Modena. Both projects share a precisely defined bi-lateral plan-form. Extending perpendicular from this axis are wings which arrange classrooms in the school, and graves in the cemetery. Either end of this central axis is marked by a circular and a square element. At the school, the circular element is a library which enters into the courtyard, and the square element is a gym hall. At the cemetery, the former is a conical grave and the latter, a monument to the war dead. Both plans refers to the axially arranged institutions of prisons, hospitals and asylums. In so doing, function is superseded by autonomous form, and the history of architecture is collapsed into a single building.

By way of conclusion it is illuminating to recall the political category of agonism posited by Chantal Mouffe in her book On the Political. We can think once again of the I/us relationship of the opening paragraphs, and more particularly the interrelated, we/they relationship. For Mouffe, the agonist principle develops from the idea of the political as a space of permanent conflict and antagonism, and hence a constancy of the we/they opposition. In antagonism there is no shared ground in the we/they opposition, so opponents are enemies. While in agonism, there is recognition of the legitimacy of the opponent, so enemy becomes adversary. Remembering that autonomy refers to notions of separation, resistance, opposition, confrontation, and critical distance, we could say that a crucial meaning of autonomy in architecture is to constantly produce a form of agonism through the production of images, texts, and buildings.

[1] See for example: Aureli, Pier V. The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture (MIT Press, 2011), Aureli, Pier V. The Project of Autonomy: Politics and Architecture Within and Against Capitalism, Reprint 2012 (Princeton Architectural Press, 2008), Hays, K. Michael. Architecture’s Desire (MIT Press, 2009),

Martin, Reinhold. Utopia’s Ghost: Architecture and Postmodernism, Again (University of Minnesota Press, 2010),

Vidler, Anthony, Histories of the Immediate Present: Inventing Architectural Modernism (MIT Press, 2008).

This essay can also be found at http://www.aefoundation.co.uk

The Fragment as a Category of Critique

![McEwan C (2012) Three Propositions [Collage]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/mcewan-c-2012-three-propositions-collage.jpg?w=701&h=1024)

McEwan C (2012) Three Propositions [Collage]

A thesis that starts with an image. A collage by the author, titled Three Propositions. Fragments of images are cut out and pasted onto cartridge paper which has been coated with a layer of white chalk, over which marks have been made using pencil and the long side of the chalk. At its centre is Aldo Rossi’s Analogical City, itself a collage that uses photocopies. Rossi’s image is around two metres square and consists of projects by Rossi, his collaborators and his references, drawn in a mixture of projection techniques: orthographic, oblique, perspective. So we get plan, elevation, perspective, and oblique sharing the same space and with equal authority. Rossi has drawn a figure, which, in my collage is displaced vertically and overlaps onto Canaletto’s vedute painting of an alternative Venice, which Rossi used to illustrate his concept of the Analogical City.

Canaletto’s painting depicts three buildings by Palladio as if they were composed in an actual cityscape. They are not. The bridge is unbuilt and the buildings either side are in Vicenza. Rossi says that an imaginary Venice is built on top of the real one. The painting is aligned with Sebastiano Serlio’s 10×10 square grid which is at the start of his Renaissance treatise in Book I On Geometry. In Book II On Perspective, Serlio illustrates the technique of perspective using the theatre sets that Vitruvius’ described in De Architettura: Tragic, Satyric, and Comical. I have cut out the one Serlio draws without the set, leaving only a gridded pattern and the outline of where the walls of the set would be, and placed it underneath the Analogical City image. On the oblique is another part of Serlio’s theatre, the semicircular seating.

On top of this and aligned with the seating is a notebook extract by Rossi. To the left of the Analogical City is Jacques Lacan’s diagram of the image-screen from the chapter “What is a Picture” in The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis. Following the diagram, Lacan says the screen is the “locus of mediation.” As Freud has said, memories are projected onto this screen as images, where they are superimposed on one another. Images are thus built on top of other images. Rossi says the city is the “locus of collective memory,” and I place Lacan’s diagram between Serlio’s geometric grid, and Rossi’s Analogical City. It directs the view toward another of Rossi’s notebook extracts in which he writes about collage in architecture, the construction of the city by parts, and the Analogical City as a compositional system that uses existing elements in new combinations, like the Canaletto painting.

The two quotations at the bottom of the collage, in their juxtaposition constitute a narrative framework:

“Forgetting Architecture comes to mind as a more appropriate title for this book, since while I may talk about a school, a cemetery, a theatre, it is more correct to say that I talk about life, death, imagination.”

Aldo Rossi A Scientific Autobiography 1981, p. 78.

“I would define the concept of type as something that is permanent and complex, a logical principle that is prior to form and that constitutes it.”

Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City 1966, p. 40.

Forgetting Fundamentals

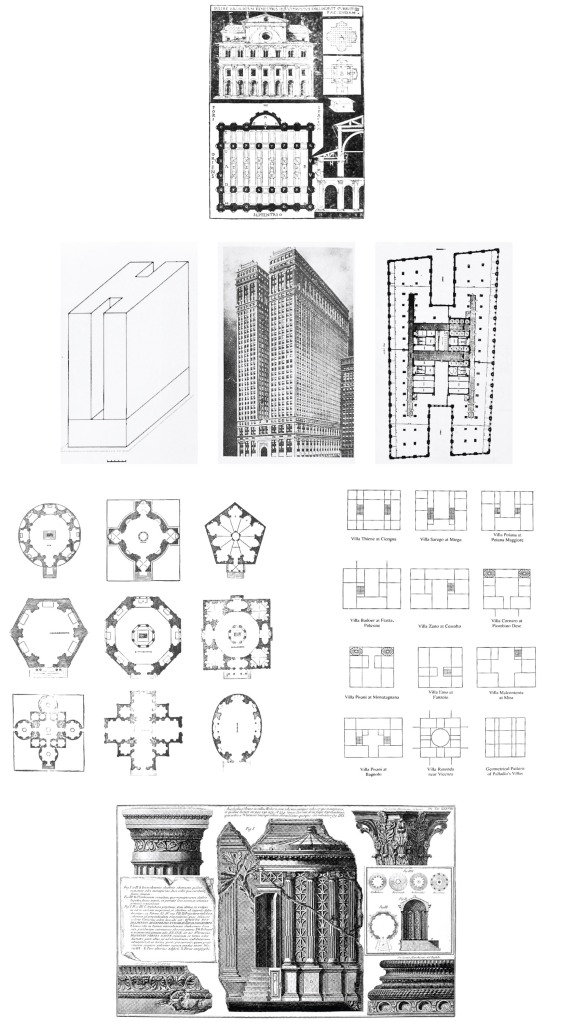

McEwan C (2012) AE Foundation Forgetting Fundamentals Montage Panel. [From top: Basilica by Vitruvius, illustrated by Cesariano (1521), Holl (1980) study of H-Type building, Serlio (c1537) centralised plan (left); Schematised plans of eleven of Palladio’s villas (c1570) via Wittkower, Piranesi (1761) study of Roman ruins with temple]

Established in May 2011, the AE Foundation provides an open independent forum for the discussion of architecture. The Foundation brings together an international community of practitioners, academics and graduates who wish to pursue architecture seriously with a view to contributing to and disseminating architectural knowledge and understanding. To, “promote the significance of the discipline, to encourage scholarship and foster an active architectural culture, in partnership with individuals in practice and academia – and to be a centre ‘par excellence’ for intelligent dialogue and debate in architectural theory, history and practice based in Scotland.”

One such discussion was undertaken during the Spring months of this year, 2012, under the general question: can we talk about fundamentals in architecture? Our exchange was at times flippant, at times philosophical, and at times biting of each other’s position. Some of us decided to formalise our thoughts in short essays. What follows is a summary. An extended version of the essay can be found on the AE Foundation website.

I started with Aldo Rossi’s rumination on the alternative title for his book A Scientific Autobiography,

“Forgetting Architecture comes to mind as a more appropriate title for this book, since while I may talk about a school, a cemetery, a theatre, it is more correct to say that I talk about life, death, imagination.”

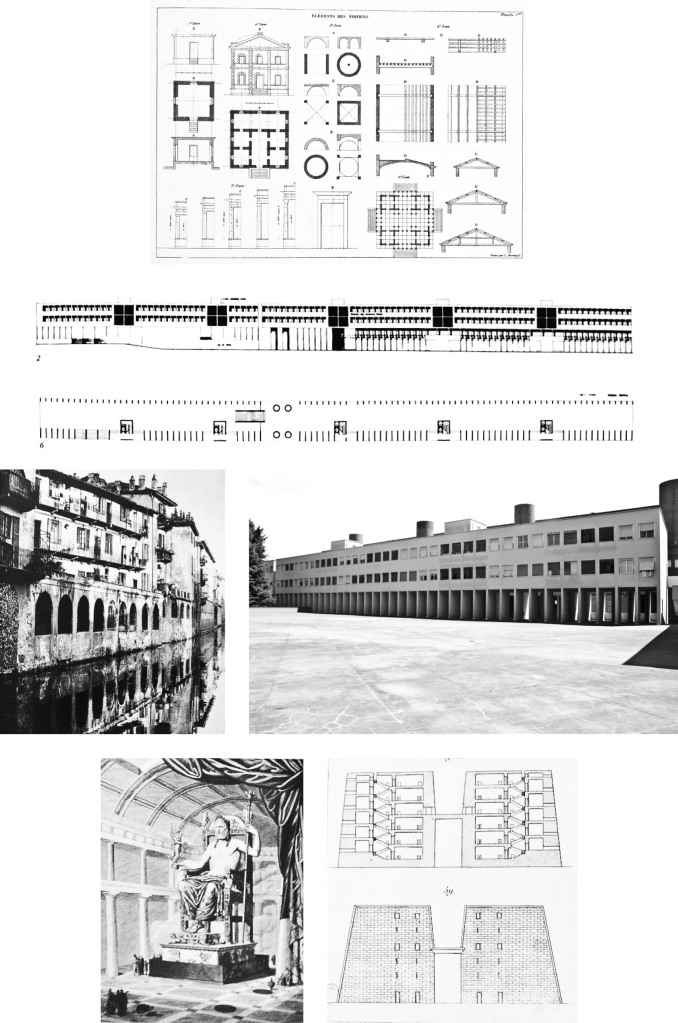

It links the building types: school, cemetery, theatre; with their conceptual analogues: life, death, imagination. In this space of association type in architecture is both material and idea. In a theory of types, we can view the process of architectural history unfolding, treatise to treatise, manual to manual, and manifesto to manifesto. That is, from Vitruvius, De architectura, Serlio and Palladio’s books during the Renaissance, to Durand’s manual which codifies buildings, Venturi’s manifesto, and the pamphlets of Holl. In Rafael Moneo’s 1978 essay On Typology, republished in a 2004 edition of El Croquis he writes that typology raises the question of the nature of the architectural work itself. In my view, it is therefore legitimate to postulate type as one place to begin a discussion about fundamentals in architecture.

For the first part, type is a way of thinking in groups, which is, analysis through classification. In architecture, the most common theories of classification by type have been according to use: national monuments, town halls, prisons, banks, warehouses, factories, as can be seen in Nikolaus Pevsner’s 1976 A History of Building Types; and according to form: centralised plan, linear arrangement, courtyard. Aldo Rossi tell us that the former understanding is limiting because the use of a building is independent from its form. Buildings evolve over time, so a warehouse becomes an apartment block, an apartment block becomes an office block, an office block becomes a brothel. Or as, for example, Atelier Bow-Wow show us in Made in Tokyo, all of these can be contained as a hybrid, so that above the warehouse is an apartment block, which is below an office, and the building terminates with a penthouse brothel.

Rossi’s quote, “I would define the concept of type as something that is permanent and complex, a logical principle that is prior to form and that constitutes it,” is significant for its location within The Architecture of the City. It mediates between a quotation by the Enlightenment architectural theorists Antoine Chrysôthome Quatremère de Quincy and Jean-Nicolas-Louis Durand. Both Quatremère de Quincy and Durand acknowledged, in different ways the relationship of memory and history in the idea of type. Quatremère de Quincy linked type with that which is archaic, elemental and primitive, and we could say to memory. Free from this metaphysical speculation, Durand’s technical understanding geometrised history. And as Rossi has said, history is the material of architecture. Thus in the adjacency of each quote we get the opposition between the conceptual and the material once more. Rossi’s quote then, mediates between the “permanent and complex,” which is archaic and elemental, something “prior to form;” and of the “logical principle,” which is that constituted by a reading of history.

And of forgetting, Rossi writes,

“In order to be significant, architecture must be forgotten, or must present only an image for reverence which subsequently becomes confounded with memories.”

Freud tells us that in forgetting, we commit something to the unconscious, where it is worked over during regression, which is an impulse to the archaic; and then to surface again when remembered, only now transformed, and reverent. The type is worked over within the collective history of architecture, to be transformed by a kind of temporal and formal regression.

McEwan C (2012) AE Foundation Forgetting Fundamentals Montage Panel 2. [From top: Durand (1805) Elements of Building, from the Précis, Rossi (1970) Gallaratese elevation, plan, photograph, Canal side tenement in Milan, Quatremère de Quincy (c1832) study for a gateway]

PhD Architecture Work in Progress 2012

Since commencing our PhD in 2009, three of the design-based researcher’s at Architecture, Dundee, have presented a modest Work in Progress, free-style exhibition. A grab from the Dundee website reads, “PhD research at Architecture, Dundee is pursued through design and focused around two interrelated themes that support priorities in creative practice and sustainability: Architecture and Intellectual Culture; and Architecture and the Environment.”

I presented study drawings of Fagnano Olona Elementary School, Italy by Aldo Rossi and used the analysis to speculate about Rossi’s analogical praxis in the Aldo Rossi in his Study montage and accompanying sketch studies. These examine the relationship between observation, memory and imagination within an analogical framework and depict the type-forms, type-elements, monuments and anonymous architecture which are at the foundation of Rossi’s praxis.

Fagnano Olona Elementary School is defined by its courtyard plan-form and axially-arranged accommodation. Within the courtyard, wide steps lead to the double height gymnasium, from which one can look toward the cylindrical library with its glazed roof. We can read this analogically and equate the gymnasium with fitness and physical health; opposite the library which is for knowledge; between these are the square and steps which is where the life of a city unfolds. The school is thus a city in microcosm.

The city is where Aldo Rossi’s thesis begins. He developed a theory of types in The Architecture of the City, which was a theory for the building forms that repeated and endured most in the history of architecture and the city. Out of this evolved his concept of the Analogical City, a conceptual framework for transposing collective types and individual monuments from architectural history to be repositioned alongside the most anonymous elements of the city. Mixed, like Canaletto’s vedute and Freud’s composite dream-image.

A Model School: Aldo Rossi’s School at Fagnano Olona

The recently established Foundation for Architecture & Education is an independent forum for the exchange of ideas about architecture and founded by Samuel Penn and Penny Lewis, who tell us, “Architects work within a rich canon. Defining the position of contemporary work in relation to the vast body of work that has gone before it is important.” The Foundation for Architecture & Education organises events, produce publications and coordinate a post-graduate course in architectural studies. The premise of which is to provide a framework in which each participant can develop their understanding of the discipline through the study of built work. The year long course is split into three parts: Model, which involves the study of a building that exemplifies a particular idea about architecture; Axiom, which demands that participants develop a clear position on their own practice in the context of a broader appreciation of shared concerns for architecture; and Locus, which offers the opportunity to design a building in a specific location. The building chosen to study in Model provides the building type to design in Locus. Each year, a new question is asked, which will be returned to in all of the work undertaken. This year is the question of size: what size should a building be?

This post is about term one Model, which concludes with an Open Review this Saturday 5th of May after a talk and presentation by architect Raphael Zuber and Christoph Gantenbein on Friday night. The building selected to study is Aldo Rossi’s school at Fagnano Olona, a small town, 40 km northwest of Milan. Designed in 1972, Rossi had built only the Segrate town square in 1965 and the Gallaratese housing block in 1970, completing the school at Fagnano Olona in 1976. Thus, it is considered one of Rossi’s early works.

The selection of this building is: first, Rossi is regarded as a significant architect and Fagnano Olona school is recognised as significant in the development of Rossi’s built and theoretical work. Second, when published, it is often illustrated in plan only and as with all of Rossi’s projects, is accompanied by beautiful sketch studies and photographs. However, the site context and sectional drawings are almost always missing. Third, the building type is sufficiently complex to use as a base for term three, Locus. Finally, and from a personal point of view, Rossi forms the foundation of my PhD, and as readers of this blog will know, there was really no other choice…Fagnano Olona school is defined by its courtyard plan-form and axially-arranged accommodation. The elevation is punctured with large square openings set in line with the internal wall thus articulating the shadow that falls on the external surface. One enters underneath a large clock, and with the adjacent conical brick chimney (containing the plant), it is like walking into a painting by de Chirico or Sironi. When I visited (see this post), it was the Summer holiday so the school was empty and the association of de Chirico was perhaps intensified by this. The chimney marks the entrance and primary axis of the school, which is organised northeast to southwest between an assembly hall and a linear pergola. Within the courtyard, wide steps lead to the double height gymnasium on the northeast, from which one can look toward the cylindrical library with its glazed roof. Double-corridor wings surround the courtyard and contain twenty-two classrooms (over two floors), staff facilities and a dining hall.

It is interesting to note a recent AR. The February 2012 issue has a short section on schools, in which Christian Kuhn offers four attributes for the building type: flexibility, clustering, common core, and connectivity. We can analyse Fagnano Olona via these attributes.Kuhn’s attribute clustering, is the division of the school into a hierarchy of smaller clusters. We can see this at Fagnano Olona in the blocks that extend outward from the central courtyard. The longer ones contain four classrooms with a corridor that is 2.5m, and repeat over two floors. The shorter ones contain three classrooms and a room off the corridor (the courtyard end), used as an informal teaching/learning space. These cluster blocks are a single storey with a 2m corridor. The blocks frame an external space with trees and grass.

Flexibility is about the granularity of room sizes and not necessarily about open-plan layout. At Fagnano Olona, the classrooms are repeated units, arranged within the four linear blocks. The other two block contain staff rooms and the dining hall. There is variation in this. At the end of each block the final classroom extends to the width of the corridor. A further subtle variation exists in the northwest end classrooms because the corridor is widened to 2.5m, from the 2m width of the southeast block. Thus, there are three classroom forms, although a fourth informal one exists as the teaching/learning space, which is roughly half the size of the small classrooms and constitutes both circulation space and space for learning.

At Fagnano Olona the common core is the central courtyard with steps. A playground, assembley space, town square and theatre. But also the informal teaching/learning spaces act quite readily as an indoor meeting place.

The final attribute that Kuhn offers is connectivity: the school as a node in a wider network of learning. He cites other learning institutions including secondary/primary school, nursery, and library at the local level; with ICT connections at the global level. At Fagnano Olona, the school includes a library, the circular element in plan, which is also part of the courtyard and adjacent to the entrance. One imagines this space to be used by the community as, for example an exhibition space.

The significance of Rossi’s work is in it’s associative links and typological investigation. Fagnano Olona is no different. A de Chirico clock and chimney mix with the pergola as a reference to the archetypal hut. The courtyard is a typological form, a town square, its steps like an amphitheatre. The library which looks like a baptistry. At Fagnano Olona my interest is in the clarity of composition and investigation of repetition and variation.

Although Rossi is often attacked for dismissing human scale, studying Fagnano Olona in detail reveals the opposite. From the over-scaled square windows which contain four smaller-sized square windows within, to the subtle difference in corridor width, the modest teaching/learning spaces and in particular I was struck by the ledge at the entrance vestibule where children can sit and shelter from the rain, peering, and thinking about that strange chimney, framed by a large square window.

Theory of Types/Dream-work: Rossi speaks to Palladio via Canaletto

Dundee School of Architecture and Duncan of Jordanstone School of Art run a Seminar series in which one (or two) PhD Candidates present their work in progress. It runs fortnightly at lunchtime, and last week was my turn.

The timing was good. I delivered a lecture to Year 3, two weeks before, which allowed me, first to consolidate my thinking on how to introduce Rossi (in broad terms); and then, Year 3 were subjected to a minor speculative foray… They may or may not have known this.

The second half of that lecture was on Rossi’s Analogical City Panel from 1976. An enigmatic montage of Rossi projects, superimposed with projects of his references, condensed, into a single image. The PhD Seminar started from here and I visually de-condensed the image, speaking about Rossi’s conversation with Palladio, via Canaletto and locating some of the primary urban types. The panel was published in Lotus International number 13, where Rossi writes of the relationship between reality and imagination, or in his words, the “dialectics of the concrete.” Imagination as a concrete thing.

”]

![Rossi A (1976) Analogical City Panel [montage diagram by McEwan C]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/rossi-a-1976-analogical-city-panel-and-montage-diagram.jpg?w=720&h=358) ”]

”]

It’s a funny type of memory, that.

![McEwan C (2012) After Architect Aldo Rossi A Scientific Autobiography [Mixed media chalk charcoal india ink on gessoed fabriano]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/mcewan-c-2012-after-architect-aldo-rossi-a-scientific-autobiography-mixed-media-chalk-charcoal-india-ink-on-gessoed-fabriano.jpg?w=720&h=488)

Something between remembering and forgetting? The dialectic that exists in memory, I mean the mis-

In The Architecture of the City architect Aldo Rossi says that the past is being partly experienced in the present. With Paris and the thesis of sociologist Maurice Halbwachs on Collective Memory in mind Rossi writes, “… the actual configuration of a large city can be seen as the confrontation of the initiatives of different parties, personalities, and governments. In this way various different plans are superimposed, synthesised, forgotten, so that the Paris of today is like a composite photograph, one that might be obtained by reproducing the Paris of Louis XIV, Louis XV, Napoleon I, Baron Haussmann in a single image.” Forgotten. This passage brings to mind one by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud who in, Civilisation and Its Discontents uses the city of Rome as an analogy to illustrate the accumulation and preservation of material in one’s unconscious. Freud writes that in mental life nothing that has once existed is ever lost. He asks us to imagine Rome to be like the unconscious, “a psychical entity with a similarly long, rich past, in which nothing that ever took shape has passed away, and in which all previous phases of development exist beside the most recent.”

And back to Rossi. He concludes A Scientific Autobiography by re-drawing twelve projects. His selection dates from 1962 to 1980, and each are signed summer, “estate 1980.” These fragments exist alongside one another in the present.

In my investigation of this, each of Rossi’s twelve projects are superimposed. Like in Freud’s Rome, a composite image is built. Starting with Gallaratese (1970) in Milan, then Segrate (1965), Modena (1979), Venice (1980) and others, each project is drawn, and then painted over. Drawn then painted over, and the process is repeated for each. Rossi’s twelve projects exist in a single image, superimposed. The present image partly experienced by the previous one, or two or three. The drawing sits somewhere between remembering and forgetting. A kind of mis-remembering.

Theory of Types/Dream-work: Work in Progress PhD Seminar 12 March

![Cameron McEwan The Architecture of Analogy PhD Seminar 2012 [poster]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/cameron-mcewan-the-architecture-of-analogy-phd-seminar-2012-poster.jpg?w=720&h=1018)

The drawings of Italian architect Aldo Rossi condense critical reflections on his own projects with studies of his architectural and everyday references, in a dense combination of lines and images. His buildings are a complex mixture of building typologies, and historical critique. Rossi’s writings are a similar hybrid of visual/textual references and reflections. Aldo Rossi’s drawings, buildings and writings are the result of an analogical thinking process. The aim of this PhD is to articulate a more precise way of understanding the deeply enigmatic processes of Aldo Rossi’s analogical thinking and practice.

This seminar presents current work in progress. It will first outline the scope of the PhD and then focus discussion on Rossi’s Theory of Types via Freud’s Dream-work.

Alliance & Rebellion: An exhibition curated by The Paper Gentlemen

![McEwan C (2012) The Paper Gentlemen Exhibition View [Photograph]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/mcewan-c-2012-paper-gentlemen-exhibition-view-photograph.jpg?w=720&h=489)

The Paper Gentlemen is a collaboration between three MArch students from the Material Unit at Dundee School of Architecture. Alliance & Rebellion is the first of a series of exhibitions which, according to the Gents, “aims to reactivate a dormant space and encourage collaboration within our varied arts community.”

The exhibition is currently on show at The Faircity Auction House, First Floor Gallery, 52-54 Canal Street, Perth.

The drawing continues the After Architect Aldo Rossi series. A montage of the twelve projects that illustrate Rossi’s A Scientific Autobiography, more of which in a forthcoming Post.

Continuing the After Architect Aldo Rossi series.”]

![McEwan C (2012) The Paper Gentlemen Exhibition Detail [Photograph]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/01/mcewan-c-2012-paper-gentlemen-exhibition-detail-photograph.jpg?w=720&h=989)

The Architecture of the City at IUAV

![McEwan C (2011) Exhibition Views of Aldo Rossi The Architecture of the City After 45 Years at IUAV Venice [photograph]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/mcewan-c-2011-exhibition-views-of-aldo-rossi-the-architecture-of-the-city-after-45-years-at-iuav-venice-photograph.jpg?w=720&h=527)

First published by Marsilio in Padova, Italy 1966, Aldo Rossi’s The Architecture of the City celebrates its forty-fifth anniversary this year with a new 2011 Italian edition. In honour of this, the IUAV University of Venice organised an international conference and exhibition, supported by the Fondazione Aldo Rossi, the MAXXI Architettura, Rome and Casabella, the journal that Rossi first wrote for and then edited.

Aiming to promote an open and wide discussion on all things Rossian, the conference first recalled the original context that generated the text; then mapped the network of translations that The Architecture of the City undertook; and finally it investigated the contemporary threads of Rossi’s legacy.

Alberto Ferlenga, Director of Doctoral Studies at IUAV and author of many texts on Aldo Rossi, introduced the conference by stating that The Architecture of the City was conceived as an, “in progress synthesis of a particular time period for urban studies.” He said that the matters mentioned by Rossi are still only partly developed and waiting for further consideration by an architectural community looking for theoretical orientation. Ferlenga compared the text to one of those “unfinished works” that Rossi continuously re-worked: a sketch, a plan, a building.

Many presentations emphasised the importance of Ernesto Rogers and Casabella had on Rossi. Serena Maffioletti, and others, said that the journal was the first to publish Rossi’s writings and was among the first to publish his designs. The individual writings for Casabella were thus the route towards The Architecture of the City. The book, then is a collage. Diego Seixas Lopes considered the fragmentary nature of The Architecture of the City to be a collage-like construction. He noted that the wide range of sources from disparate fields intertwined with mentions to Milizia (Enlightenment architecture), Poete (French geography), de Saussure (linguistics) and memories of cities walked by Rossi. Showing preliminary photographs of the making of the book, it looks similar to the way Rossi makes the Blue Notebooks. Freehand writing, with sketch drawings and photocopies of “things” pasted together.

The Verbal and Non Verbal”]![Rossi A (1966) My own copy of the 1982 The Architecture of the City and McEwan C (2011) Rossi's Modena Cemetery [Photomontage]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/rossi-a-1966-my-own-copy-of-the-1982-the-architecture-of-the-city-and-mcewan-c-2011-rossis-modena-cemetery-photomontage.jpg?w=720&h=429)

I learned via Elisabetta Vasumi Roveri that the alternative title of The Architecture of the City was to be The City Planning Manual. Uncannily timely, my own contribution noted the alternative title of Rossi’s second book A Scientific Autobiography was to be Forgetting Architecture. I used the article by Adam Caruso titled Whatever Happened to Analogue Architecture and published in AA Files 2009 as my starting point to investigate a lineage of Analogue Architecture from Aldo Rossi to the contemporary Swiss architects Christian Kerez and Valerio Olgiati. I outlined the article by Caruso, who offered a concise section on Aldo Rossi’s two tenure’s at ETH Zurich in the 1970s (Kerez and Olgiati are one step removed from being students of Rossi), and then considered the opposition offered by Carl Jung to Sigmund Freud on analogical thinking. Jung said that analogical thinking was both verbal and non verbal, which invites speculation on the relationship between writing and built form. I suggested the image mediates. Similarly when we speculate on Rossi’s alternative title, Forgetting Architecture, the opposite of forgetting is remembering; and via Freud it is mis-remembering that mediates. Equating these two mediating principles, I offered an analogical reading of Kerez and Olgiati, and suggested thus the contemporary state of Analogue Architecture. A controversial implication. The title of my own contribution was rather cheekily Whatever Happened to Analogue Architecture? Perhaps I should drop Caruso an email…

and Caruso A (2009) Whatever Happened to Analogue Architecture [article title] Mis-remembering the Image. Somewhere between the verbal and non verbal”]![Rossi A (1989) Untitled [painting] and Caruso A (2009) Whatever Happened to Analogue Architecture [article title]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/rossi-a-1989-untitled-painting-and-caruso-a-2009-whatever-happened-to-analogue-architecture-article-title.jpg?w=720&h=416)

Now for the exhibition. The publishing history of The Architecture of the City was presented as original books, artefacts; around which, a timeline according to Rossi’s Blue Notebooks was charted. Extracts of which were scattered as loose fragments. A little bit lost looking.

”]![Aldo Rossi Extracts from the Blue Notebooks at The Architecture of the City After 45 Years IUAV Venice [photograph by McEwan c (2011)]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2011/11/aldo-rossi-extracts-from-the-blue-notebooks-at-the-architecture-of-the-city-after-45-years-iuav-venice-photograph-by-mcewan-c-2011.jpg?w=720&h=527)

The publishing history reads: Italy 1966, Spain 1971, Germany 1973, Portugal 1977, Italy 1978, France 1981, Spain 1982, USA 1982, Greece 1987, Japan 1991, China 1992 (2 of), Brazil 1995, Italy 1995, Portugal 2001, Italy 2006, and the new 2011 Italy Edition. It is interesting to note the front covers. For example, the first edition of Italy 1966 superimposes a Renaissance Ideal City over an aerial landscape; Italy 1978 shows the Mausoleum of Hadrian (later transformed into the Castel Sant’Angelo). While France 1981 the Analogical City appears five years after it was first presented, then Japan 1991 the Mausoleum again after it was used by Eisenman in the 1982 USA introduction where he juxtaposed a drawing of a labyrinth, setting up ideas about journey and transformation. The China 1992 shows the Analogical City for the second time. The new Edition for 2011 is from an ArtForum article titled Fragments and depicts a storyboard dated 1987 New York.

And those enigmatic Blue Notebooks. Text-based notes, diagrams of objects and projects, self portrait sketch studies, fragments of train tickets, photocopies of newspapers and photographs of views are pasted within. Indeed, I took pleasure in finding out that the Notebooks measure 220mm by 175, when laid flat.

These are just a few highlights in a short Blog Post. The conference was dense with knowledge, intensely focused and in true Rossian style, it was both lucid and murkily ambiguous. I am grateful for the opportunity to share such a platform and thank those who selected my proposal. Indeed, especially to Eamonn Canniffe who forwarded me the Call for Papers and Graeme Hutton for allowing me the short leave. My only criticism is that there was very little questioning of Rossi in general, and considerably less questioning directed at the speakers, in particular. Perhaps this is okay but resistance is welcome, and criticism directed at the individual research presentations should have been encouraged.

![McEwan C (2012) Aldo Rossi in His Study [Expo View]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/mcewan-c-2012-aldo-rossi-in-his-study-expo-view.jpg?w=720&h=489)

![McEwan C (2012) Aldo Rossi in His Study [Sketch studies]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/06/mcewan-c-2012-aldo-rossi-in-his-study-sketch-studies.jpg?w=720&h=325)

![Rossi A (1972-76) Fagnano Elementary School [Photograph McEwan C 2011]](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/rossi-a-1972-76-fagnano-elementary-school-photograph-mcewan-c-2011.jpg?w=720&h=1083)

![Rossi A (1972-76) Fagnano Elementary School [Re-drawn by McEwan C 2012] Rev A](https://cameronmcewan.files.wordpress.com/2012/05/rossi-a-1972-76-fagnano-elementary-school-re-drawn-by-mcewan-c-2012-rev-a.jpg?w=720&h=497)

2 comments